When the captain and crew of the whaling ship Essex departed Nantucket in August of 1819 they had no way of knowing that their two and a half year routine journey would be riddled with the worst luck to ever befall a whaling ship and the tale of the journey would follow them into history.

When the captain and crew of the whaling ship Essex departed Nantucket in August of 1819 they had no way of knowing that their two and a half year routine journey would be riddled with the worst luck to ever befall a whaling ship and the tale of the journey would follow them into history.

The whaling ship Essex left Nantucket with twenty-one hands on board on August 12, 1819 bound for prosperous whaling waters in the Pacific Ocean. Captain George Pollard and First Mate Owen Chase were experienced whalers and accomplished seafarers and the 87 foot long, 238 ton Essex, although small for a whaler, had been a prosperous ship for its owner(s). Several days after departing Nantucket, Essex ran headlong into a two day storm that severely damaged the ship and nearly capsized her. Captain Pollard made the fateful decision to continue toward the Pacific rather than return to Nantucket or put into an east coast port for repairs. Because of this decision, the journey was very slow and Essex made her turn around Cape Horn and into the south Pacific five weeks later.

Pollard and Chase decided to head toward the Galapagos Islands. Sailing north along the South American coast Essex encountered no whales and the crew began to speak of bad omens due to the incident involving the storm. Upon their arrival to the Galapagos Islands, they discovered that there were no whales to be found in the usually whale rich waters. Captain Pollard, believing a tip that he had received from another whaling ship, turned Essex out to sea. Sailing for over nine days to an area 2500 miles southwest of the Galapagos Islands, the captain and crew finally began to see whales spouting in the area. They readied their three whaleboats and equipment and leaving the safety of Essex began pursuing the whales.

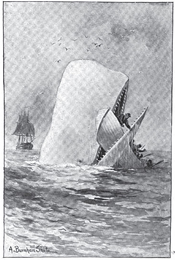

All three whaleboats were launched. Captain Pollard piloted the first, First Mate Chase piloted the second boat and Second Mate, Obed Hendricks piloted the last. Pollard and the second Mate proceeded south while Chase pursued a whale pod to the north. Chase’s crew harpooned a whale that eventually turned and damaged the whaleboat forcing Chase to return to the Essex for repairs. Once the whalers were on board of Essex, Chase spotted a large sperm whale that he would later say was over 85 feet long.

"I turned around and saw him (sperm whale) about one hundred rods (550 yards) directly ahead of us, coming down with twice his ordinary speed (around 24 knots or 44kph), and it appeared with tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect. The surf flew in all directions about him with the continual violent thrashing of his tail. His head about half out of the water, and in that way he came upon us, and again struck the ship." …First Mate, Owen Chase.

"I turned around and saw him (sperm whale) about one hundred rods (550 yards) directly ahead of us, coming down with twice his ordinary speed (around 24 knots or 44kph), and it appeared with tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect. The surf flew in all directions about him with the continual violent thrashing of his tail. His head about half out of the water, and in that way he came upon us, and again struck the ship." …First Mate, Owen Chase.

The big whale rammed Essex, crushing the bow and throwing Chase and the crew into a panic. Knowing the severety of their plight, Chase ordered the steward and crewmembers to gather all of the supplies that could be removed and to secure any navigational aids that could be found. As the supplies were being brought to the deck Chase and another crewmember prepared sails for the fourth and last remaining whaleboat. Captain Pollard saw the commotion and returned to Essex as she was slowly going down. They quickly launched the fourth boat, divided the supplies between the three boats and watched from a distance as Essex sank from sight.

The three boats sailed south for over a month until they reached Henderson Island a small uninhabited island that had an abundance of fresh water and birds. The men spent a week on the island gathering food, fishing and storing water for the 3000 mile journey west to South America. Three of the crewmembers elected to stay behind on Henderson Island when Pollard and the others set sail on December 31. By early January the supplies had run out on all three boats and the crewmembers began to die. On the 11th the boat piloted by Owen Chase became separated during a storm. They would be rescued on February 18th by a whaling ship.

On board of the two boats piloted by Pollard and Second Mate Hendricks, the situation was just as desperate. Their supplies had run out in early January and the Hendricks boat became separated later in the month, which was never seen again and their fate unknown. They continued to sail on the tradewinds until February 23rd when they were rescued by the whaling ship Dauphin. The three men who had stayed behind on Henderson Island would be rescued on April 12th and the eight survivors of the Essex were reunited in South America. At the time of their rescues, it was discovered that the men on both the Pollard and Chase boats had survived by eating the remains of their dead crewmates. The final accounting of the 21 officers and crew of Essex was eight survivors, three lost at sea, three buried at sea and seven crewmembers consumed (including Pollard’s cousin, Owen Coffin). It had been 95 days since Essex had sunk.

The eight men returned to Nantucket and by all accounts all but one returned to whaling. Owen Chase would later write an account of the incident titled Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex. His two sons would also be Nantucket whale fishermen, one of which sailed with Herman Melville and even gave him a copy of his father’s book. This would become the inspiration for the book Moby-Dick, or The Whale, published in 1851.