"The steam was so hot I could scarcely breathe. I groped my way out of this place as quick as I could. It took me a moment to realize what had happened. A boiler had blown up. Within a few minutes the ship caught fire. When the crowd fully realized what had happened men began to jump into the water by the hundreds."

-Robert Talkington, 9th Indiana Cavalry

S. S. Sultana: America's Titanic

History has recorded that on April 14, 1865, five days after Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse to General Ulysses S Grant, the assassin, John Wilkes Booth shot President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theater, resulting in the president’s death the following morning. A nationwide manhunt began for Booth and his co-conspirators which ended twelve days later at Garrett’s Farm when Booth and David Herold were surrounded by members the 16th New York Cavalry. Sergeant Boston Corbett fired a single shot into Garrett’s barn hitting Booth in the neck. The shot paralyzed him from the neck down. He died on the porch of Garret’s farm in the predawn hours of April 26. During the height of the manhunt for the conspirators, Lincoln’s funeral train left Washington, D.C. on April 21, for a 1,600 mile, twelve day journey to the President’s final resting place at Oak Ridge Cemetery, in Springfield, Illinois.

The Civil War was over, Lincoln was dead, his assassins were dead or being rounded up and a nation mourned. It is very easy to understand how, amid the swirl of media surrounding the events of April, 1865, that newspapers throughout the nation, and the Americans who read them, missed the sinking of the S.S. Sultana. The largest maritime disaster in U.S. history and the fifth largest in recorded human history.

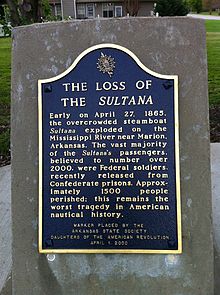

S. S. Sultana: Historic Marker

The S.S. Sultana was a side-wheeled steamship constructed in Cincinnati, Ohio, and launched on January 3, 1863. The U.S. Customs registry listed Sultana at 260 feet long, with a 42 foot beam and weighing 660 tons. Her paddlewheel was 34 feet in diameter and she was outfitted with four 18 feet long newly designed lightweight tubular boilers specially created to give her added horsepower in the strong currents of the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee Rivers. Upon her launching from the John Litherbury Shipyard in Cincinnati, the vessel was cleared by Customs to carry a total of 1,000 tons. According to most accounts of the ship, Sultana legally accommodated 376 passengers and crew. Many of the staterooms were very elegant with custom appointments for first class passenger service. Sultana’s design and weight displacement allowed the steamer to draw only 34 to 37 inches of water fully loaded, and made her perfect for passenger and cargo transport in shallow waterways. She was outfitted with the most modern fire safety equipment available, including high pressure fire hoses, multiple fire pumps, fire buckets and fire axes. Furthermore, Sultana was outfitted with 76 life rings in the event of water born disaster. The S.S. Sultana was considered to be, by those in the business of river transportation, one of the finest vessels ever built and she was put into service with a regular passenger and cargo schedule between New Orleans and St. Louis.

S.S. Sultana pulled away from the docks at New Orleans the same day that Lincoln’s funeral train pulled away from the train station in Washington, D.C., April 21, 1865. The Captain and Ships Master, J.C. Mason was subsequently one of three investors who had purchased Sultana from her original owner in March of 1864. Capt. Mason had made many voyages up and down the Mississippi River and had full faith in the seaworthiness of Sultana but as fate would have it the ships engineer, J.W. Kennison discovered that one of the steamer’s boilers began to leak a few hours before arriving at Vicksburg, Mississippi. Instead of replacing the damaged boiler, Captain Mason ordered Master Boilermaker, R.G. Taylor, of Vicksburg, to perform the necessary repairs that would allow him to get Sultana to St. Louis. While the repairs got underway in Vicksburg, Mason began to take on Unions prisoners of war from Confederate POW camps at Camps Fisk, Cahawba and Andersonville, as part of a government contract that he had received. Under the contract, Mason and his partners would receive five dollars for each Union soldier he loaded onto Sultana’s decks for the long trip upriver to Illinois and Ohio. It was later reported by a witness on board of the S.S. Sultan; “The ship was grossly overloaded as the great steamer pulled away from the dock at Vicksburg.” However, Captain Mason believed that the 2,300 POW’s made the vessel look overcrowded but did not believe that she was overloaded. The S.S. Sultana steamed away from Vicksburg at 9 p.m. on April 24 with 2,400 passengers and crew, 20 tons of sugar and approximately 40 head of livestock. Although the big ship appeared to be struggling, she lumbered her way up the Mississippi River.

S. S. Sultana Tragedy

On the night of April 26, Sultana pulled into Memphis to unload some of her 20 tons of sugar. Once released from the dock, Capt. Mason steamed to the Arkansas side of the river to take on additional coal for the next leg of Sultana’s trip up the Mississippi to St. Louis. After departing at around midnight, the Union soldiers who had helped unload the sugar and load the coal sought out small spaces on the already overcrowded deck in which to lie down and sleep. At 2 a.m., about seven miles upriver from Memphis, tragedy struck when two of Sultana’s four boilers exploded. The shrapnel from the explosion caused the other two boilers to explode as well, sending a rush of steam, fire, boiler shrapnel and fiery debris over the ship. The scene was chaos.

“… but I was sleeping soundly again, when, I was suddenly awakened by the hot cinders flying in my face, and starting up, found the blankets we had thrown over us to be on fire. So deep had been my sleep that I had not heard the report of the bursting boiler which has been described as a sound which seemed to be the groans of the world being rent in twain. Timbers were flying in every direction together with the remnants of the boiler, and fire raged on the shattered vessel. What should we do? To stay on board meant to be burned to death for every moment the flames were gaining headway. And surely to leap into the depths of a river which having burst its levees, had spread its water over a breadth of five miles, could mean no less than death.

Some already were leaping into the water and I tried to decide which course to pursue or which kind of death to choose, the flames were coming closer and closer; now almost all had abandoned the vessel. Seizing a stick of wood, I jumped off into the water.”

Several times was I pulled under water by others drowning and, finding that the wood could not aid me and spying a cable chain, I grasped the latter as a last means of hope. Holding firmly to this with my hands, and catching my toes in the lower links, I managed to keep my head above the water. My hands soon became so stiff that I could not hold to the chain that way, so I clung to it with my arms. As I hung there, fearing every moment to lose my hold and drop into eternity, as I heard the cries of the drowning and felt that their fate would soon be mine……”

“The cries of the drowning were pitiful -- heart rending. Those of one Irishman I can never forget. His face had been terribly crushed by the flying missiles, his nose being entirely split open. Still he managed to keep his head above water and when someone said that a boat was coming to our rescue, he cried out again and again, ‘0 the Lord’s a good Lord, we'll all be saved.’ But, alas, we could not all be saved at once; and after gathering up a load of the wounded and drowning, the boat pulled away and we saw it no more.”

“I hung there, with body grown numb through exhaustion, until seven o'clock In the morning, when the citizens from the Arkansas side of the river came with a raft to our rescue. I was perfectly helpless when taken out of the water and it was only by the aid of brandy and skillful hands that I was brought to life. The poor Irishman, I learned, did not live but a short time after our rescue. Afterwards we were taken back to Memphis to the hospital and I lay there until the second evening after our arrival, seeing not one face of the eight of my company who had started on the boat, and thinking that they were all lost except myself.”

“Over 1,700 of the noble boys lost their lives on that terrible night.”

- Uriah Mavity, 40th Indiana

At about 3 a.m. the southbound steamer Bostonian happened upon the burning Sultana, which had drifted to the western bank of the Mississippi River and was sinking into a shallow mud bank. Passengers were clinging to trees along both shores of the river as well as floating on debris from the ship. The Captain of the Bostonian steadied the steamer as passengers and crew began to pull survivors from the frigid waters. It was then that the loss of life from the explosion and fire became evident to the rescuers. The explosion had been heard seven miles away in Memphis and the northbound steamer Arkansas, which had just left the dock at Memphis when the explosion occurred, was searching for the source of the fire and smoke as she steamed up the Mississippi. Within minutes of the arrival of the Bostonian, other boats began to arrive on the scene and would continue to join the rescue effort until well after 8 a.m. The task of pulling survivors and the dead was daunting. Rescuers noted that many of the survivors and the dead had suffered severe burns in the blast. Many of the victims that had survived the initial blast without injury fell victim to hypothermia and drowning.

In the aftermath of the explosion and sinking of Sultana, the injured passengers and survivors were taken downriver to Memphis and the task of removing the dead from the river began. Several investigations ensued. The U.S. Customs and Department of the Army’s investigations cited several causes for the disaster including Captain Mason’s overloading the vessel, a catastrophic failure of the repaired boiler and “mismanagement of water levels within one, if not several of the boilers”. Capt. Mason, whose body was found by the searchers, was not held personally responsible for the disaster, however, Captain Fredrick Speed, the assistant Adjutant General of the Department of the Mississippi and the officer in charge of transportation for the POW’s was charged with negligence in the overloading of the vessel. Furthermore, the U.S. Custom’s death total from the accident was listed as 1547, a count that did not include passengers who were listed as missing by other passengers. Those reports, coupled with the U.S. Customs official report take the death toll closer to 1700 lives lost.

The survivors of the S.S. Sultana disaster began to meet for a reunion for the first time in 1867. The survivors had a lot to discuss in the 1912 reunion, held in Knoxville, for the R.M.S. Titanic had sank 15 days earlier, killing 1,502 souls. The last reunion was held in 1930, in which only one survivor showed. It was 65 years to the day of the disaster.

{fcomment}