The First American Born Architect

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

On August 12, 1781, at the height of the American Revolution in South Carolina, Robert Mills was born in Charleston. He studied in Charleston before traveling to Washington, D.C., in 1800, to apprentice with the famed Irish architect, and builder of the White House, James Hoban. In the years to following his time with Hoban, Robert Mills traveled around designing some of America’s most historically significant buildings including the following:

On August 12, 1781, at the height of the American Revolution in South Carolina, Robert Mills was born in Charleston. He studied in Charleston before traveling to Washington, D.C., in 1800, to apprentice with the famed Irish architect, and builder of the White House, James Hoban. In the years to following his time with Hoban, Robert Mills traveled around designing some of America’s most historically significant buildings including the following:

- the Burlington County Prison in Mt. Holly, New Jersey, in 1811

- the First Presbyterian Church of Augusta, Georgia and the Monumental Church in Richmond, Virginia, in 1812

- the octagonal First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia in 1813

- St. John’s Episcopal Church in Baltimore, Maryland and the First Baptist Church of Baltimore in 1817

- several buildings of the University of South Carolina in 1818

- the First Baptist Church of Charleston, SC in 1820

- the South Carolina State Hospital in 1821

- the Fireproof Building in Charleston in 1827

Mills was a master of architecture who designed and built dozens of homes, churches and government buildings throughout America. When he wasn’t building engineering marvels, he enjoyed writing books on the subject authoring at least 6 books on architecture before his most prolific project, the world’s tallest stone structure and tallest obelisk, the Washington Monument. Construction of the monument began in 1848, however, Robert Mills, who died in 1855, would never see its completion in 1884.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Frontpage Articles

- Hits: 4342

In the late 1890’s Christian Protestant groups, mainly Baptist, Congregationalist and Methodist in rural areas of the north, and isolated pockets in deep-south America, began a movement which focused on the elimination of alcohol in the United States. Organizations such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the Anti-Saloon League believed that alcohol was destroying the morals of Americans and that it needed to be eradicated from society. Following World War I the movement gained a foothold as a major lobbyist in Washington, D.C. In 1920 the United States government passed the 18th Amendment which prohibited the manufacturing and sale of alcohol, and the Volstead Act which regulated the laws surrounding Prohibition. In response to the overwhelming demand for alcohol from post World War I Americans, the criminal underworld found new and creative ways to supply the underground Gin Joints, Speakeasy’s and Blind Tigers which served the illegal liquor.

On October 29, 1929 the social condition in America went from bad to worse when the entire U.S. banking system collapsed in a single day. Within a month of the collapse, America had slipped into the Great Depression. Overnight millions of jobs were lost, entire fortunes dwindled and companies became insolvent. The most realistic statistic for the first three years of the Great Depression has the unemployment rate hovering around thirty percent. Due to a lack of jobs, money, opportunities and alcohol, crime escalated in America. Prohibition and the Great Depression gave rise to a new breed of criminal. The Depression and Prohibition Era criminals were far more brazen and violent than pre WWI criminals, and, like millions of jobless, homeless Americans, they viewed the government, banks and the greed of wealthy American’s as the reason for all of the pandemonium.

John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, Machine Gun Kelly, Bonnie and Clyde and Pretty Boy Floyd emerged as the most notorious of the Depression and Prohibition Era criminals.

Their crimes were sensationalized in newspapers and on film. Legend states that Dillinger, who was listed as the first “Public Enemy #1” by the Department of Justice in 1934, enjoyed the 1931 James Cagney movie, “The Public Enemy”, however Dillinger was in prison during the 1931 release of the film. On the other side of the coin, media outlets of the era were sensationalizing the exploits of great lawmen of the times such as J. Edgar Hoover, Elliot Ness and Melvin Purvis. Elliot Ness and his “Untouchables” had brought down Chicago mob boss, Al Capone in 1931 and Ness was later assigned to investigate the gruesome Cleveland Torso Murders in Ohio. J. Edgar Hoover, the charismatic Director of the Bureau of Investigation (later the FBI), had arrested and deported subversives, radicals and suspected anarchist during the first World War and assembled a forensics team to investigate the Lindberg baby kidnapping. The Lindberg baby case would be the birth of forensic science in criminal cases and these great lawmen and advances in crime fighting techniques would be needed to reign in criminal behavior during the 1930’s. The crime wave created by Prohibition and the Great Depression would reach a fevered pitch in the first month 1932 and would become known as the Thirty Months of Mayhem.

1932

Jan. 14, 1932 – Pretty Boy Floyd robs a bank in Castle, Oklahoma.

Pretty Boy Floyd

Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd

(February 3, 1904 - October 22, 1934)

Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd began his career at the age of 18 in St. Louis, Missouri when he was convicted of stealing less than four dollars from a Kroger grocery store. Upon his release, Floyd was accused of killing a man who had allegedly killed his father many years earlier however local authorities were unable to secure a conviction. This, including his conviction and three year imprisonment for robbing a payroll truck in St. Louis drew the attention of some of the mid-west’s most notorious criminals. After his release, Floyd began working as muscle for a Kansas City crime syndicate and reportedly boasted that he would never again see the inside of a prison.

Charles Floyd acquired the name “Pretty Boy” when a witness to an early Floyd bank robbery, in Ohio, described him as “a mere boy – a pretty boy”. Newspapers of the times began referring to him by the name that, as legend states, he hated and was known to react violently when called the name in person. He reached the pinnacle of his lawlessness during the Thirty Months of Mayhem and upon the death of John Dillinger, Floyd was named Public Enemy #1 by the FBI. The popular version of Charles’s final gun battle states that when Floyd was cornered in an Ohio cornfield, he drew his .45 caliber pistol and opened fire on Melvin Purvis, his three FBI agents and members of the East Liverpool, Ohio police. Purvis returned fire and killed Floyd but this is one example of media sensationalism of the era. Pretty Boy Floyd was actually brought down by a two shots to the leg by East Liverpool policeman, Chester Smith. Floyd was lying on the ground writhing in pain when Melvin Purvis ordered one of his agents, Herman Hollis, who would later be killed by Baby Face Nelson, to “Fire into him!”

Jan. 27, 1932 - Machine Gun Kelly kidnaps banker, Howard Wolverton in South Bend, Indiana.

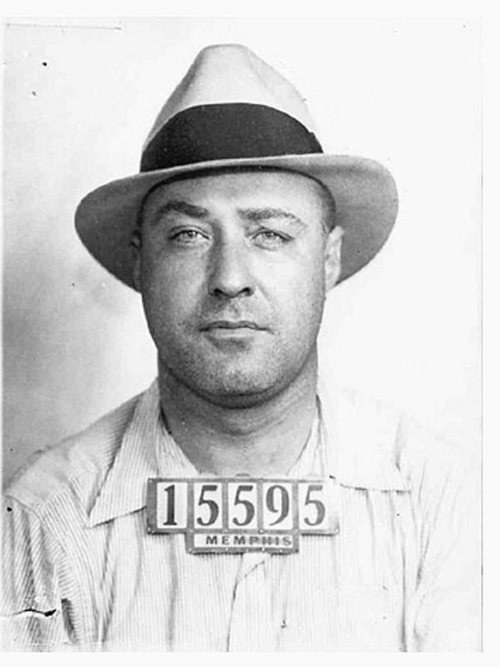

George Celino Barnes AKA Machine Gun Kelly

George Celino Barnes, aka “Machine Gun Kelly”

(July18, 1895-July 18, 1954)

According to all available research George Celino Barnes, aka George “Machine Gun”Kelly was a low level bootlegger and petty thief in Memphis, Tennessee during the 1920’s and 30’s. His exploits gained him a lot of attention by Memphis Police in 1928 causing him to change his name to George R. Kelly and slip away to Oklahoma. After serving a three year sentence for bootlegging in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Kelly returned to Memphis and graduated to kidnapping and bank robbery. He married Kathryn Thorne, who gave him a Thompson .45 caliber machine gun as a wedding gift. The name “Machine Gun” Kelly found its way into history following his first bank robbery, during which George randomly fired four dozen rounds from his Thompson machine gun. No one was hurt in the robbery however the newspapers and law enforcement labeled him as a violent, deadly, machine gun wielding criminal. The most famous crime of Machine Gun Kelly’s career was the kidnapping of Oklahoma City banker and businessman, Charles Urchel. The caper netted Kelly and his gang nearly $200,000 in ransom money.

George and Kathryn were hiding out in a Memphis home when Kathryn slipped away long enough to contact the Memphis police regarding their hideout. The FBI was notified and a raid was planned for the next day. George and Kathryn were caught without weapons, or incident, however legend states that when agents entered the residence, George screamed out, “Don’t shoot G-men, Don’t shoot!” More recent research reveals that during the incident, Kathryn may have embraced a handcuffed George and said, “These G-man will never leave us alone!” George R. Kelly would never rejoin the Thirty Months of Mayhem. He spent his remaining years in Alcatraz and Leavenworth Prisons.

Feb. 17, 1932 - Baby Face Nelson escapes from Illinois State Penitentiary and begins bootlegging on the west coast with notorious bank robber, Eddie Bentz.

Lester Gillis AKA Baby Face Nelson

Lester Gillis, aka “Baby Face Nelson”

(December 6, 1908 – November 27, 1934)

Lester Joseph Gillis, aka George Nelson, aka Baby Face Nelson was only twelve when he began his criminal career. By the age of eighteen, Lester was committing armed robbery and home invasions. It is during these years that he became associated with the Chicago crime syndicate and was being referred to as “Baby Face” Nelson because of his youthful features. In 1932 he was convicted of robbery and sentenced to life in prison however he escaped before arriving Joliet Penitentiary. He stayed in seclusion only briefly then began robbing banks throughout the Midwest and for a short time partnered with John Dillinger for a string of bank robberies.

George Baby Face Nelson, facing a life sentence, appears to have had nothing to live for and no conscience about killing federal agents, police officers or innocent bystanders. While on the run in Nevada, Nelson was enlisted as a hit man. In contrast, George Nelson was very close to his family and often had his wife and children brought to him while he was in hiding between bank robberies. When George lay dying, following The Barrington Battle (Barrington, Illinois), during which Baby Face Nelson was shot seventeen times, his wife, Helen Gillis stood at his deathbed holding his bloodied hand. Helen, fearing the FBI, went on the run only to be named as the first female Public Enemy #1.

Mar., 1932 - Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker form a gang consisting of Buck Barrow, W.D. Jones, Raymond Hamilton and Henry Methvin.

Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

Bonnie Parker & Clyde Barrow

(Oct. 1, 1910 – May 23, 1934) and (March 24, 1909-May 23, 1934)

The story of these two ruthless, calculating killers began in February of 1932 when Clyde Chesnut Barrow was released from Eastham Prison in South Texas. Clyde had spent most of his life behind bars for petty theft and car theft. While out on parole in 1930, Clyde had met Bonnie Elizabeth Parker in west Dallas. He was subsequently rearrested for robbing a grocery store in Dallas. When he was released in 1932, Clyde sought out Bonnie Parker. Clyde vowed that he would never return to prison. With Bonnie at his side he formed a gang which included his brother, Buck Barrow and sister-in-law, Blanche Barrow. Bonnie and Clyde drove stolen cars from town to town robbing stores and banks and killing any law enforcement officials that attempted to stop them.

The fabled pair spent their entire relationship on the run from police, involved in shootouts, committing robberies and committing murder. The most famous of all the shootouts came in 1933 at the Red Crown Tourist Court in Platte City, Missouri when local police opened fire on the tiny brick cottage the gang was hiding out in. Clyde returned fire with his Browning Automatic Riffle as the gang loaded into a car in an attached garage. Bonnie and Clyde barely escaped but Buck and Blanche were both wounded. The villainous couple continued their murderous rampage until they were ambushed by Texas Ranger, Frank Hammer in Bienville Parish, Louisiana. The coroner for Bienville Parish, Dr. J.L. Wade stated that he found seventeen bullet wounds in Clyde Barrow and twenty-five in Bonnie Parker. In all 130 rounds were dispensed by the six lawmen.

|

April 7, 1932 |

Pretty Boy Floyd kills Sherriff, Erv Kelley in Bixby, Oklahoma. Floyd is shot in the ankle during a battle with police. |

|

April 21, 1932 |

Pretty Boy Floyd robs a bank in Stonewall, Oklahoma. |

|

April 27, 1932 |

Clyde Barrow kills businessman, John Bucher during a robbery. |

|

Aug. 5, 1932 |

Bonnie and Clyde gun down officer Eugene Moore in Oklahoma. |

|

Sept. 21, 1932 |

Machine Gun Kelly and Eddie Bentz rob a bank in Colfax Washington. |

|

Sept. 29, 1932 |

Machine Gun Kelly and Eddie Bentz rob a bank in Holland, Michigan. |

|

Oct. 11, 1932 |

Bonnie and Clyde kill Howard Hall during a general store robbery in Sherman, Texas. |

|

Nov. 1, 1932 |

Pretty Boy Floyd robs a bank in Sallisaw, Oklahoma. This would be the first of three banks robbed by Floyd in November of 1932. Henryetta, Oklahom on the 7th and Boley, Oklahoma on the 23rd. |

|

Nov. 30, 1932 |

Machine Gun Kelly robs a bank in Tupelo, Mississippi. |

|

Dec. 26, 1932 |

Bonnie and Clyde kill Doyle Johnson while stealing a car. |

1933

|

Jan. 6, 1933 |

Bonnie and Clyde shoot and kill Deputy Sheriff, Malcolm Davis during an ambush by law enforcement officials. |

|

April 13, 1933 |

The Barrow Gang are in a shootout with law enforcement in Joplin, Missouri. |

| April 27, 1933 | Bonnie and Clyde kidnap two merchants of Ruston, Oklahoma. The merchants are released unharmed in Arkansas. |

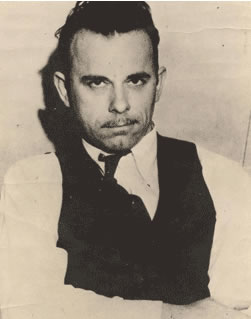

John Dillinger

John Dillinger

(June 22, 1903 – July 22, 1934)

When John Dillinger was an adolescent, his father noticed that his young son had a rebellious streak. The Indianapolis grocer moved his family to Mooresville, Indiana in the hopes that John would not be tempted into a life of crime by the bright lights of the city or the nefarious characters that he had began to associate with. This, however, did not work. Shortly after arriving to Mooresville, Dillinger began to draw the attention of local law enforcement. He believed that he needed to separate himself from his oppressive father, and avoid the law, so he joined the U.S. Navy but he quickly deserted and returned to Mooresville. After marrying Beryl Hovious in 1924, John tried to settle down, however it was not long before he was planning the robbery of a local grocery store. That caper earned Dillinger a sentence of ten to twenty years in the Indiana State Prison at Michigan City. On May 10, 1933, John Dillinger is released from Michigan City Prison after serving nearly ten years for robbing a grocery store of fifty dollars.

The life of John Dillinger was larger than the legends that have been created over the last eighty years. He escaped from jail using a wooden gun, robbed over a dozen banks, staged a prison break, and stole nearly $500,000 within a fourteen month time period, making him the most predominant, and most wanted during the Thirty Months of Mayhem.

|

June 10, 1933 |

John Dillinger robs a bank in New Carlisle, Ohio…..The same day, Bonnie Parker is severely burned in a car crash near Wellington, Texas. |

|

June 17, 1933 |

Kansas City Massacre. Pretty Boy Floyd, Vernon Miller and one other gunman try to free gangster, Frank Nash from the FBI. Three police officers, one FBI agent and Frank Nash are killed during the shootout. |

| June 23, 1933 | The Barrow Gang kills Marshal Henry Humphrey of Alma, Arkansas during ambush and shootout. |

| July 7, 1933 | Clyde Barrow breaks into the National Guard armory at Enid, Oklahoma, stealing a stockpile of weapons. |

| July 19, 1933 | The Barrow Gang shoots their way out of an ambush at the Red Crown Tourist Court in Platte City, Missouri. |

| July 22, 1933 | Machine Gun Kelly kidnaps an Oklahoma City businessman, Charles Urchel. |

| July 24, 1933 | The Barrow Gang is ambushed at Dexfield Park in Dexter, Iowa. Buck Barrow is killed. W.D. Jones and Bonnie Parker are wounded.Buck’s wife, Blanche Barrow is wounded and captured. |

| Aug. 18, 1933 | Baby Face Nelson and Eddie Bentz rob the people’s Savings Bank in Grand Haven, Michigan. |

| Sept. 22, 1933 | Dillinger is arrested in Dayton, Ohio. He is transferred to Lima, Ohio. |

| Sept. 26, 1933 | Using a gun previously smuggled in by Dillinger, 10 men escape from Indiana State Prison. |

| Oct. 12, 1933 | Three escapees from Indian State Prison free John Dillinger from the Allen County Jail in Lima, Ohio. Sherriff Jesse Sarber is killed. |

| Sept. 26, 1933 | Machine Gun Kelly is captured in Memphis, Tennesee. In October of that year he would be sentenced to life in prison. His kidnapping trial holds a place in history as having several U.S. first. The Kelly trial was the first to be filmed. His trial was first federal crime case to be solved by the FBI, with J. Edgar Hoover as Director, and the first kidnapping case that was tried as a federal crime. |

| Oct. 23, 1933 | Baby Face Nelson robbed the 1st National Bank in Brainard, Minnesota. |

| Oct. 23, 1933 | Dillinger and his gang rob the Central National Bank, in Greencastle, Indiana. |

| Nov. 7, 1933 | Vernon Miller is found dead in Detroit, Michigan |

1934

|

Jan. 15, 1934 |

Dillinger robs a bank in East Chicago, Indiana, killing Officer William O’Malley. |

| Jan. 16, 1934 | Bonnie and Clyde free four inmates from Eastman Penitentiary in Houston, Texas. |

| Jan. 25, 1934 | John Dillinger is capture in Tucson, Arizona and extradited to Ohio to stand trial for the murder of Sherriff Sarber. |

| March 3, 1934 | John Dillinger escapes from the Allen County Jail using a wooden pistol. The escape is believed to have been financed by Baby Face Nelson and his gang. |

| March 6, 1934 | Dillinger and Baby Face Nelson rob the Security Bank & Trust in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. |

| March 13, 1934 | Dillinger and Nelson robbed a bank in Mason City Iowa. Shortly after the robbery, Nelson and one other gang member flee to Reno, Nevada. |

| March 24, 1934 | Baby Face Nelson and one other accomplice kill a primary witness to the trial of two of Nelson’s former bosses. |

| March 31, 1934 | Bonnie and Clyde steal a car in Shreveport, Louisiana. |

| April 1, 1934 | Bonnie and Clyde gun down two highway patrolman in Grapevine, Texas. |

| May 23, 1934 |

Bonnie and Clyde are killed by Texas Ranger, Frank Hammer, in Bienville Parish, Louisiana. One of the law enforcement officers, Dallas County Deputy Sherrif Ted Hinton, who was present at the ambush, was quoted as saying. "Each of us six officers had a shotgun and an automatic rifle and pistols. We opened fire with the automatic rifles. They were emptied before the car got even with us. Then we used shotguns... There was smoke coming from the car, and it looked like it was on fire. After shooting the shotguns, we emptied Thethe pistols at the car, which had passed us and ran into a ditch about 50 yards on down the road. It almost turned over. We kept shooting at the car even after it stopped. We weren't taking any chances."

|

| June 22, 1934 | John Dillinger is celebrating his birthday when he discovers that he has been listed as Public Enemy # 1 by the U.S. Department of Justice. |

| June 30, 1934 | Dillinger robs a bank in South Bend, Indian. |

| July 22, 1934 | John Dillinger is killed in an ambush in Chicago by FBI agents, led by Melvin Purvis. Anna Sage, a prostitute and sometimes girlfriend of Dillinger had tipped off federal agents. When the coupled exited the theater, agents moved in and fired on the outlaw killing him in an ally off of Lincoln Avenue. |

| Oct 22, 1934 | Pretty Boy Floyd is killed by Melvin Purvis in a corn field near Clarkson, Ohio |

| Nov. 27, 1934 | Baby Face Nelson is wounded in a gun battle in Barrington, Illinois. He died later that day in Niles Center, Illinois. |

Thirty Months of Mayhem died with Baby Face Nelson!

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Frontpage Articles

- Hits: 5498

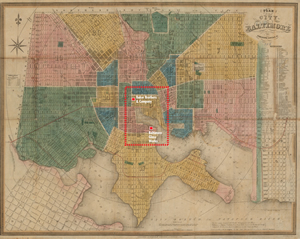

CRIMES FOR POE: Part I - The Death of Edgar Allan Poe

On the morning of October 3, 1849, at approximately 10:00 a.m., a printer for the Baltimore Sun newspaper, Joseph W. Walker, happened upon a disheveled man sitting on a sidewalk along East Lombard Street, between Exeter and High Streets in downtown Baltimore, Maryland. Walker immediately recognized the man as famed poet and author Edgar Allan Poe. Walker’s discovery of the enigmatic, incoherent Poe was, without contestation, the beginning of one of America’s most mysterious stories:

The Death of the Father of Modern Detective Fiction.

The inscrutable and talented Edgar Allan Poe had spent the summer of 1849 on a lecture tour to raise money for a proposed writer’s magazine, Stylus. In late May, he was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for a brief time before traveling to Richmond, Virginia, where he stayed until September 27. Contemporary accounts of his final days in Richmond are scattered; however, it appears that Poe was preparing to travel to Philadelphia to edit the poetic works of Marguerite St. Leon Loud, titled Wayside Flowers (1851). He wrote a letter to his aunt Maria Clemm describing his travel plans for late September: “On Tuesday I start for Philadelphia to attend to Mrs. Loud’s Poems—& possibly on Thursday I may start for New York. If I do I will go straight over to Mrs. Lewis’s and send for you. It will be better for me not to go to Fordham—don’t you think so? Write immediately in reply and direct to Philadelphia For fear I should not get the letter, sign no name and address it to E.S.T. Grey Esqr . . . Don’t forget to write immediately to Philadelphia so that your letter will be there when I arrive.” The same day Poe wrote to Maria Clemm, he also wrote a letter to Loud explaining that he had been delayed, postponing his original departure date of September 7. He confirmed that he planned to be in Philadelphia on September 25 to begin editing her works.

The inscrutable and talented Edgar Allan Poe had spent the summer of 1849 on a lecture tour to raise money for a proposed writer’s magazine, Stylus. In late May, he was in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for a brief time before traveling to Richmond, Virginia, where he stayed until September 27. Contemporary accounts of his final days in Richmond are scattered; however, it appears that Poe was preparing to travel to Philadelphia to edit the poetic works of Marguerite St. Leon Loud, titled Wayside Flowers (1851). He wrote a letter to his aunt Maria Clemm describing his travel plans for late September: “On Tuesday I start for Philadelphia to attend to Mrs. Loud’s Poems—& possibly on Thursday I may start for New York. If I do I will go straight over to Mrs. Lewis’s and send for you. It will be better for me not to go to Fordham—don’t you think so? Write immediately in reply and direct to Philadelphia For fear I should not get the letter, sign no name and address it to E.S.T. Grey Esqr . . . Don’t forget to write immediately to Philadelphia so that your letter will be there when I arrive.” The same day Poe wrote to Maria Clemm, he also wrote a letter to Loud explaining that he had been delayed, postponing his original departure date of September 7. He confirmed that he planned to be in Philadelphia on September 25 to begin editing her works.

Poe researchers have advanced the idea that E.S.T. Grey, Esq., was a fictitious name used by the writer as one way to account for his paranoia, and Poe would only have done so because he was suffering from a long-term delusional state brought on by his alcohol and drug use. His actions around the time that he wrote his letter to Clemm tend to discount the thought that he was suffering from long-term effects from intoxicants. By available accounts, Poe had become a member of the Richmond branch of the Temperance Movement and had stopped drinking. He set about making plans to embark on the Stylus endeavor and had several lectures booked at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond.

Poe researchers have advanced the idea that E.S.T. Grey, Esq., was a fictitious name used by the writer as one way to account for his paranoia, and Poe would only have done so because he was suffering from a long-term delusional state brought on by his alcohol and drug use. His actions around the time that he wrote his letter to Clemm tend to discount the thought that he was suffering from long-term effects from intoxicants. By available accounts, Poe had become a member of the Richmond branch of the Temperance Movement and had stopped drinking. He set about making plans to embark on the Stylus endeavor and had several lectures booked at the Exchange Hotel in Richmond.

There is no question that Poe suffered greatly in the early part of June 1849; however, there is clear evidence through his writings that he was being plagued by something akin to a reoccurring seizure that would bring about unique psychological side effects such as depression, hallucinations, and uncontrollable fits of anger. Two letters that Poe sent to Clemm in June reflect that the condition from which he was suffering would come and go, leaving the writer confused about his actions. The first letter Poe sent to Clemm, dated June 7, 1849, describes a debilitating illness: “I have been so ill—¬have had the cholera, or spasms quite as bad, and can now hardly hold the pen.” The condition that Poe writes about had passed by mid-June, and he wrote a second letter to Clemm 12 days later, explaining the true state of his condition: “You will see at once, by the handwriting of this letter, that I am better—much better in health and spirits. Oh, if you only knew how your dear letter comforted me! It acted like magic. Most of my suffering arose from that terrible idea which I could not get rid of—the idea that you were dead. For more than ten days I was totally deranged, although I was not drinking one drop; and during this interval I imagined the most horrible calamities . . . All was hallucination, arising from an attack which I had never before experienced—an attack of mania-a-potu. May Heaven grant that it prove a warning to me for the rest of my days. If so, I shall not regret even the horrible unspeakable torments I have endured.”

Oscar Penn Fitzgerald, author, newspaper editor, and a bishop of the Methodist church had the occasion to encounter Edgar Allan Poe in late summer of 1849. His recollections on the meeting, published in Bishop Fitzgerald’s Life Story, do not paint a picture of a downtrodden, drunken, and longsuffering poet: “I have a very vivid impression of him as he was the last time I saw him, on a warm day in 1849. Clad in a spotless white linen suit, with a black velvet vest and a Panama hat, he was a man who would be notable in any company. I met him in the office of the Examiner, the new Democratic newspaper which was making its mark in political journalism.” Fitzgerald went on to describe Poe’s outward appearance on that day. “Through the good offices of certain parties well known in Richmond, Poe had taken a pledge of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks. His sad face—It was one of the saddest I ever saw—seemed to brighten a little, as a new purpose and fresh hope sprang up in his heart.” In relation to his writing abilities, Fitzgerald goes on to explain that before leaving Richmond, Poe held a lecture on his essay The Poetic Principle. The lecture packed the meeting rooms of the Exchange Hotel, with 300 patrons paying $5 apiece. Fitzgerald recounted, “I had the pleasure of hearing it read, and remember how forcibly I was struck with his tone and manner of delivery.” His recollection does not evoke a man who was delusional, paranoid, or suffering from the long-term effects of alcohol. In contrast, this account by Bishop O.P. Fitzgerald describes a man who was clear in thought and basking in his literary success.

Oscar Penn Fitzgerald, author, newspaper editor, and a bishop of the Methodist church had the occasion to encounter Edgar Allan Poe in late summer of 1849. His recollections on the meeting, published in Bishop Fitzgerald’s Life Story, do not paint a picture of a downtrodden, drunken, and longsuffering poet: “I have a very vivid impression of him as he was the last time I saw him, on a warm day in 1849. Clad in a spotless white linen suit, with a black velvet vest and a Panama hat, he was a man who would be notable in any company. I met him in the office of the Examiner, the new Democratic newspaper which was making its mark in political journalism.” Fitzgerald went on to describe Poe’s outward appearance on that day. “Through the good offices of certain parties well known in Richmond, Poe had taken a pledge of total abstinence from all intoxicating drinks. His sad face—It was one of the saddest I ever saw—seemed to brighten a little, as a new purpose and fresh hope sprang up in his heart.” In relation to his writing abilities, Fitzgerald goes on to explain that before leaving Richmond, Poe held a lecture on his essay The Poetic Principle. The lecture packed the meeting rooms of the Exchange Hotel, with 300 patrons paying $5 apiece. Fitzgerald recounted, “I had the pleasure of hearing it read, and remember how forcibly I was struck with his tone and manner of delivery.” His recollection does not evoke a man who was delusional, paranoid, or suffering from the long-term effects of alcohol. In contrast, this account by Bishop O.P. Fitzgerald describes a man who was clear in thought and basking in his literary success.

On the eve of his departure from Richmond, Poe visited the home of physician Dr. John R. Carter, a lifelong friend of the Poe family. Upon leaving Dr. Carter’s office, the writer left a copy of Thomas Moore’s Irish Melodies, often misidentified as Irish Rhapsodies, and mistakenly picked up Carter’s rattan cane, which concealed a sword. Dr. Carter’s impression of Poe’s lecture on The Poetic Principle echoes that of Bishop Fitzgerald, and both men attest that Poe was in possession of $1,500 when he departed Richmond. In 1849, 1,500 US dollars were worth approximately $42,000 against the 2015 US dollar. Understandably, some Poe researchers believe him to be the target of a mugging and beating that would have left him in a disheveled state on Lombard Street six days after he departed for Philadelphia.

Edgar Allan Poe left Richmond bound for Philadelphia on the night of September 27. The most reputable account of Poe’s travels places him on board of a ship sailing from Richmond to Baltimore, where he would catch the train to Philadelphia. Poe’s whereabouts for the next six days have become the stuff of legend, as there is no practical theory that can explain where he was, who he was with, what he may have endured, or how he came to be on a Baltimore street. Neilson Poe, who was married to Josephine Clemm, the sister of Poe’s wife, Virginia, wrote a letter from Baltimore, dated several days after Poe’s death. He claimed that “where he [Poe] spent the time while he was here, or under what circumstances, I have been unable to ascertain.”

Due to his literary successes in the 1840s, Poe was a prominent figure in most northeastern cities in which he traveled. When Walker made his fateful discovery, Poe was not impeccably dressed in his trademark black coat and black velvet vest. In contrast, he was wearing a dirty and worn-out sack coat, unpolished shoes that were worn down at the heel, and a ragged straw hat. His face and clothing were covered in dirt, and he had a hint of whisky on his breath. In a very strange twist to the descriptions of Poe’s condition, he was found on Lombard Street, holding the very expensive and identifiable cane of Dr. Carter. To Walker, Poe appeared to be intoxicated or in some state of delirium, as the writer spoke incoherently and maintained an uncompromising state of lassitude. Walker recognized that Poe was in dire trouble and helped the feeble man into a tavern at 44 East Lombard Street, which belonged to Cornelius Ryan. Often referred to as Gunner Hall, Ryan’s Tavern was a polling location for Baltimore’s Fourth Ward, and the day that the famed troubadour was found was voting day in Maryland. Although the weather in Baltimore was rainy on that Wednesday, Ryan’s Tavern, and ostensibly Lombard Street, were bustling with people traveling to and from the polls.

Once Walker settled Poe at a table in Ryan’s Tavern, he asked the wavering patient if there was anyone that he should contact. Through his haziness, Poe said the name of at least one person—Dr. Joseph Evans Snodgrass, a physician, editor, and leader of the Temperance Movement in Baltimore during the 1840s. Walker sent a letter to Dr. Snodgrass, which read:

“Dear Sir, There is a gentleman, rather the worse for wear, at Ryan’s 4th ward polls, who goes under the cognomen of Edgar A. Poe, and who appears in great distress, & he says he is acquainted with you, and I assure you, he is in need of immediate assistance, Yours, in haste, Jos. W. Walker.”

When Snodgrass arrived, he was accompanied by Henry Herrin, the husband of Poe’s aunt Elizabeth Poe Herring. The two men deduced that Poe, who had been sober for some time due to his pledge, had gone on an alcohol-fueled bender and declared the writer to be drunk. His uncle Henry Herring, who had his own animosities toward Poe, refused to take him to his home to care for him. Joseph Snodgrass, Joseph Walker, and Henry Herring loaded the semiconscious writer into a carriage bound for Washington University Hospital, located on Baltimore’s Washington Hill.

At Washington University Hospital, Poe was placed in a room normally reserved for people who had fallen ill from consuming alcohol; however, his attending physician, Dr. John J. Moran, did not believe that the writer was drunk or suffering from an alcohol-induced calamity. In accordance with the symptoms Poe exhibited, the 25-year-old Moran, who had received his degree from the University of Maryland in 1845, believed that Poe had been the victim of a physical attack, during which he had sustained significant head trauma. This supposed assault would have left his famous patient sufficiently disoriented and lethargic. Moran, as the only witness to Edger Allan Poe’s condition during the days prior to his death, stated that he had offered brandy to the patient in an attempt to calm him, but the beverage was staunchly refused. He questioned Poe on several occasions in an attempt to ascertain what had befallen him, but no explanations for the six days prior were to be had from the disoriented man. In the years that followed Poe’s death, Moran stated that Poe, clearly in a deteriorating state, would go into fits of dark, foreboding language that made very little sense to the physician. He would maintain within lectures and his writings on the subject of Poe’s death that Poe’s wild rants included, “Language cannot tell the gushing well that swells, sways and sweeps, tempest-like, over me, signaling the larm of death,” and “My best friend would be the man who gave me a pistol that I might blow out my brains.” Through the years, Moran’s stories of Poe tended to vary; however, the physician stood his ground and maintained his famous patient did not suffer from an alcohol-related event. He noted in a lecture many years after the artist’s death: “I have stated to you the fact that Edgar Allan Poe did not die under the effect of any intoxicant, nor was the smell of liquor upon his breath or person.”

On Thursday, October 4, Neilson Poe arrived at the hospital in an attempt to visit the ailing poet. He was told that the patient was too excitable to see him. Neilson Poe left the hospital, only to return the next day. He describes his actions in relation to the events in a letter to Maria Clemm dated October 11, 1849:

“As soon as I heard he was at the college, I went over, but his physicians did not think it advisable that I see him, as he was very excitable. The next day, I called and sent him changes of linen, etc.”

Edgar Allan Poe lay in a lonely, semi-dark room on the second floor of the Washington University Hospital for four long days, drifting in and out of consciousness and speaking to imaginary entities within his room. Moran had no way of knowing that in 1847, Poe was diagnosed by Dr. Valentine Mott of New York, as having lesions on his brain, and Dr. John Francis had diagnosed the author with a weak heart in 1848. Because of these two conditions, which were unknown to Moran, he could not ascertain the cause of his peculiar patient’s condition and was unable to render any type of relief. He watched helplessly as Poe slowly slipped deeper and deeper into his condition. Moran later stated, “When I returned, I found him in a violent delirium, resisting the efforts of two nurses to keep him in bed. This state continued until Saturday evening when he commenced calling for one ‘Reynolds,’ which he did through the night up to three on Sunday morning.” Several hours later, at around 5:00 a.m., Edgar Allan Poe was dead. Neilson Poe, who had tried to ease the suffering of his famous cousin through fellowship and clean, fresh linens mourned, “And I was never so shocked, as when, on Sunday Morning, notice was sent to me that he was dead.”

“Our city was yesterday shocked with the announcement of the death of Edgar A. Poe, Esq., who arrived in this city about a week since after a successful tour through Virginia, where he delivered a series of able lectures. On last Wednesday, election day, he was found near the Fourth ward polls laboring under an attack of mania a potu, and in a most shocking condition. Being recognized by some of our citizens he was placed in a carriage and conveyed to the Washington Hospital, where every attention has been bestowed on him. He lingered, however, until yesterday morning, when death put a period to his existence. He was a most eccentric genius, with many friends and many foes, but all, I feel satisfied, will view with regret the sad fate of the poet and critic.”

—The New York Herald, October 9, 1849

A Baltimore newspaper, Clipper, had heralded death of Edgar Allan Poe on October 8, 1849, by announcing that he had died of “congestion of the brain.” Researchers have long attributed Poe’s congestion of the brain as an after effect of the writer’s alcohol use, but this diagnoses are, at best, misdirected. It is common knowledge that Poe was a chronic alcoholic, and long-term alcoholism can affect the brain, but early-19th-century scientists used congestion of the brain to describe numerous then-inscrutable conditions, from epilepsy to stroke. Dr. William A. Hammond, who dedicated his life to the study of neurological diseases, separated alcoholism, Grave’s disease, opiate poisoning, typhus, and other types of viral diseases from his study of diseases of the brain in A Treatise on Diseases of the Nervous System. First published in the Journal of Psychological Medicine in 1871, Hammond describes swelling of the brain from long term alcoholism as an after effect of the alcoholism and not an actual brain disorder that causes death. This assertion hints that Poe died from an actual brain disease such as epilepsy, encephalitis, hydrocephalus, or meningioma, which is a slow-growing calcified mass that develops in the membrane between the skull and the brain. Furthermore, Poe had been alcohol free for at least four, and possibly six months. This one fact, and Dr Hammond’s contemporaneous study of the human brain, undermines the theory that he had literally drank himself to death.

The funeral of Edgar Allan Poe was not a grand affair that lavished praise and honorifics upon the enigmatic writer as his body passed through the streets of Baltimore. In fact, it was a much smaller affair, with only nine people in attendance on October 8, 1849. At approximately 4:00 p.m. on that day, renowned author and the “Father of Modern Detective Fiction” was laid to rest in an unlined mahogany coffin within an unmarked grave near his grandfather David Poe Sr. in the Westminster Presbyterian Church graveyard, on the corner of West Fayette and North Greene Streets.

In 1873, a school teacher from Baltimore, Sara S. Rice, began to gather money for a proper monument for Edgar Allan Poe, who, in death, had become a literary giant. Two years after the monument was erected, officials of Westminster Presbyterian decided to move Poe’s remains to a new burial site closer to the front of the churchyard. During that move, George W. Spence, the sexton who oversaw the first burial of Poe, reported that the author’s skeletal remains were in excellent shape; however, when he picked up Poe’s skull, a hard, calcified mass was found rolling around inside of the cavity. Spence reported, “[H]is brain rattled around inside just like a lump of mud.” Another witness who relayed the story of Poe’s exhumation to a Baltimore newspaper relayed, “[T]he cerebral mass, as seen through the base of the skull, evidenced no signs of disintegration or decay, though, of course, it is somewhat diminished in size.”

The calcified mass discovered inside of Edgar Allan Poe’s skull, in 1875, may be the definitive clue as to the cause of the author’s death. Unfortunately, this, and undisputedly, all of the theories surrounding his death, fall into to the dubious category of conjecture. Maybe Poe was beaten so badly for his money that the head trauma sent him into a state of delirium that would inevitably cause his death. There is compelling evidence to suggest that such an event could have occurred. He could have consumed so much alcohol and opiates during his lifetime that the blood vessels in his brain ceased to function properly, eventually killing him. It is possible, but the probability of such an event has always been in question by the medical community. A brain tumor such as meningioma that created extreme hallucinations and bipolar disorder–like symptoms could have caused him to black out for six days, depositing Poe on a Baltimore street, and eventually, his death bed. Unsupported documentation from the time of his exhumation seems to support such a scenario, or perhaps Poe died of something deeper, darker, and beyond the understanding of modern-day professional, and amateur, Poe researchers. Poe enthusiast and history book editor Abigail Fleming has stated that he may have died from “long-term untreated illness, alcoholism, and a tortured, unfulfilled soul.” Although gentle in its delivery, her theory is as plausible as beatings, tumors, and now-common diseases that were misdiagnosed. Furthermore, of all of the theories that have been proposed in the last 165 years, her theory is the most Poe-esque.

The Father of Modern Detective Fiction left the world with many great works of the Romantic era, but moreover, he left behind one of the greatest mysteries in United States history: