- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1700

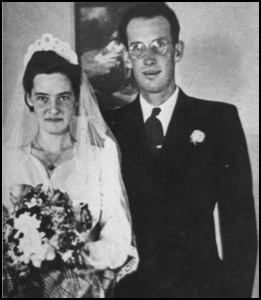

Elsie and Archie Mitchell

On the morning of May 5, 1945, Elsie Mitchell, the wife of Pastor Archie Mitchell, took her Sunday school class for a picnic near Bly, Oregon. The picnickers consisted of Elsie, her husband Archie, and five children, Edward Engen, age 13, Jay Gifford, age 13, Joan Patzke, age 13, Dick Patzke, age 14, Sherman Shoemaker, age 11. As Pastor Mitchell was parking the car, Elsie and the children discovered a large balloon with a peculiar device attached to it, lying in a field. The party neared the device. There was no way for Elsie to know that the balloon and device was a Japanese weapon of war. It exploded killing all six instantly. By all accounts, the six victims of the Bly explosion were the only casualties inflicted on American soil by the Japanese.

WWII Balloon

From November, 1944 to April, 1945 the Japanese Army released over 9000 hydrogen filled balloons into the jet stream. The plan was headed up by Major General Sueyoshi Kusaba, commander of the Imperial Army’s research laboratory. A research team had discovered the jet stream by accident and realized that Japan’s winter winds flowed across the Pacific Ocean to the United States. The team first outfitted a rubber coated silk, hydrogen filled balloon but soon discovered that the silk would leak. They choose instead a dense paper derived from mulberry trees. The device by which the explosive ordinance would be carried was designed to not only explode upon landing but keep itself inside of the jet stream using ballast bags of sand and a valve to release hydrogen. With the sandbags, explosives and device, the total payload on the balloon, upon liftoff, was nearly one thousand pounds.

In the six month time period of the attempted attack on America, approximately 9300 balloons were released by the Japanese Army. It is widely believed by researchers that only 300 ever made it to the U.S., Canada or Mexico. In the U.S., sightings of balloons or downed balloons were reported in seventeen states. When the strange balloons began to show up in America, pilots were ordered to shoot them down. A few, however, did not get shot down. Several of these exploded in the forest of California, Oregon and Washington causing wildfires. Several of the balloon missiles landed and did not detonate. Over time these were rounded up by military authorities and destroyed, except for a few that are presently located in museums.

Elsie Mitchell Tombstone

In the U.S., the military and government did everything within their power to keep media outlets from reporting on the “Japanese Fire Bombs”, although this would and could put Americans at risk, as in the case of Mrs. Elsie Mitchell and her Sunday school class. In Japan it was reported that the bombs were hitting key targets and cities and that thousands were dead or injured and that the American moral was very low. This was clearly the propaganda machine at work against its own people for it is known that only six people lost their lives. Mrs. Elsie Mitchell was honored with a monument.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1949

In the four years between September of 1934 and April of 1938, fear gripped the city of Cleveland, Ohio. A serial murderer roamed the streets preying on the poor transients that made their home in the shanty town of Kingsbury Run on the shore of the Cuyahoga River. This individual embarked upon a killing spree that lasted four years and left five women and seven men brutally murdered and dismembered around Cleveland. “The Butcher of Kingsbury Run” would become another of history’s sensationalized, unidentified killers befitting of the ranks of Jack the Ripper, the Zodiac killer and the murderer of Elizabeth Short, a.k.a. “The Black Dahlia”.

In the four years between September of 1934 and April of 1938, fear gripped the city of Cleveland, Ohio. A serial murderer roamed the streets preying on the poor transients that made their home in the shanty town of Kingsbury Run on the shore of the Cuyahoga River. This individual embarked upon a killing spree that lasted four years and left five women and seven men brutally murdered and dismembered around Cleveland. “The Butcher of Kingsbury Run” would become another of history’s sensationalized, unidentified killers befitting of the ranks of Jack the Ripper, the Zodiac killer and the murderer of Elizabeth Short, a.k.a. “The Black Dahlia”.

By most accounts, the “Torso Murders” began in September of 1935 when the bodies of two male victims were discovered in Kingsbury Run. Both of the men had been decapitated and one was identified as Edward Andrassy, a local street thug. There were some investigators in Cleveland who believed the murders had begun a year earlier when a female body was discovered floating in Lake Erie at Euclid Beach. The “Lady of the Lake” was found decapitated and could not be identified. Investigators in the case would later associate the discovery of the Lady of the Lake with the discovery of the seventh victim whose body was also found at Euclid Beach twenty-nine months later.

The years of the torso murders contained the darkest and most gruesome crimes Cleveland would ever see. Several of the victims had been decapitated where they stood, but others, investigators believed, had been killed, decapitated or dismembered, drained of blood, and then thoroughly cleaned at an undiscovered location before being dumped in Kingsbury Run. Both the Sheriff of Cuyahoga County, Martin O’Donnell, and Cleveland’s Public Safety Director, Elliot Ness (The Untouchables), had different theories about the perpetrator’s motives and methods. O’Donnell believed that the gruesome crimes were being committed by someone in Kingsbury Run who could blend back into the landscape after killing and beheading his victims, or someone who had a “laboratory” near Kingsbury where he could take his abducted victims. The sheriff had two of his detectives searching for the location of the killings but found nothing that would lead them to the Butcher. The sheriff then focused his attention on Frank Dolezal, who confessed to killing Florence Polillo, a forty year old prostitute and the third victim. It was learned, through the investigation, that Polillo frequented a saloon that had been a popular spot for the only other two identified victims, Rose Wallace (Victim #8) and Edward Andrassy (Victim # 2) . It was later discovered that the confession had been beaten out of Dolezal and that his descriptions of the crime did not match up to the condition in which Polillo’s body had been found. Dolezal recanted his confession and hung himself in jail before he could go to trial.

Elliot Ness believed that the killer was an individual with some medical training who would be found among Cleveland society. He also believed that the killer was a large man, able to overpower his victims quickly. At one of the “on site” murders, a large footprint, later identified as a size twelve shoe, was found on the ground around the victim. He put three of his best people on the investigation. One of them, Virginia Allen, uncovered Dr. Francis Sweeney as a possible suspect. Sweeney had been in the medical field as far back as the First World War and suffered from severe mental illness. Ness personally interviewed Sweeney, a large man with size twelve shoes, but could not get a confession or denial from him regarding the murders. Sweeney would eventually fail two lie detector tests, however, the machines and tests were in their infancy and not admissible as evidence. Ness believed that there was not enough evidence to hold or charge Dr. Sweeney. He would later recount the story in an interview with journalist, Oscar Fraley. Ness noted that the killings stopped after Sweeney had himself institutionalized and would say that he “drove out” the Mad Butcher of Kingsbury Run.

Many others in the law enforcement and historic research communities do not believe that the torso murders ended, or even began with Sweeney. Four decapitated and dismembered bodies were found in a swampy area near New Castle, Pennsylvania in the years prior to 1935 and three bodies were found near McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania in the spring of 1940. One male victim was discovered in New Castle in 1936 during the height of the Cleveland torso murders leading most investigators to believe that the Butcher of Kingsbury Run was, as Sheriff O’Donnell believed, someone who could blend into the transient population and was connected to the Pennsylvania murders by the railways that ran throughout the region.

The Butcher of Kingsbury Run has been blamed for murders dating from 1921 to 1950 and has even been accused, by some investigators, of the 1947 killing of Elizabeth Short, the Black Dahlia. Through all of the conjecture, the Butcher has, in the spirit of Jack the Ripper and Zodiac, kept his identity and his motives secret and will forever remain an unnamed individual in the strange history of America.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1656

St. Albans Raid

On the afternoon of October 10, 1864 a young man checked into a hotel in St. Albans, Vermont. In the days that followed, leading up to October 19, more strangers would check into hotels within the tiny town. The unsuspecting townspeople had no way of knowing that while Civil War battles named Westport, Hatchers Run, Burgess Mill and Allatoona raged, their little town was about to be the subject of one of history’s strangest Civil War raids. The friendly young man and the other strangers who arrived in the town were Confederate Lieutenant Bennett H. Young and his band of twenty-one cavalrymen. They had planned to rob the town, burn it, take the townspeople captive then escape to Canada having committed the northern most battle of the Civil War and finding a place in America’s Strange History.

Lieutenant Young was chosen for the mission for his bravery during Morgan’s Raid in which Confederate General John Hunt Morgan and 2462 cavalrymen rode nearly 1000 miles from Sparta, Tennessee to Salinesville, Ohio, raiding towns in Kentucky, Indiana and Ohio. The raid ended in Salinesville following the defeat of General Morgan by forces under the command of Union General James Shackelford. General Morgan and most of his officers, including Lieutenant Bennett Young were captured. They were confined in the Ohio Penitentiary in Columbus, Ohio. Young and four other confederates escaped the penitentiary and swiftly made their way to Canada. There, Young contacted Confederate agent George Sanders who planned and financed the raid on St. Albans with a goal of securing the town’s money for the Confederacy.

At 3 p.m. on the afternoon of October 19, the twenty-one Confederate raiders simultaneously began to rob the three banks in St. Albans, taking $208,000. After the robbery, the raiders gathered the townspeople in the center of town and attempted to burn the town however their fires did very little destruction. Lieutenant Young and his cavalrymen escaped back into Quebec, Canada having left two St. Albanians wounded and one dead. Upon their arrival in Canada the raiders were captured by Canadian government force and placed in a Montreal jail.

The Canadian court, wishing to remain neutral, refused to extradite the raiders back to United States citing that Young and his cavalrymen were under military orders from the Confederate government therefore they had committed no crime under U. S. law as they were soldiers, not criminals. The court would also determine that Young’s Raiders had not broken any Canadian laws so they were released. Bennett Young would rise to the rank of General and served the Confederacy as an agent in Canada until the end of the war. He would be refused amnesty by President Andrew Johnson and would not be allowed to return to the U.S. until 1868.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1625

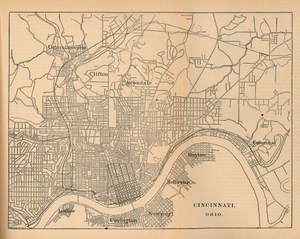

Over-The Rhine, When Beer Was King

By Michael D. Morgan

Copyright 2010

Publisher, History Press

Over-The-Rhine, When Beer Was King is a must read for any historian. Michael D. Morgan’s incredible forensic analysis of the history of the City of Cincinnati, its inhabitants and beer making history proves that Mr. Morgan has a true passion for the city that he calls home. His knowledge of Cincinnati’s breweries is unlimited and has helped bring attention to the preservation of the historic buildings in the Pendleton area of the city, called Over-the Rhine in the first half of the 19th century.

StrangeHistory.org is proud and excited to have Over-The-Rhine in its vast reference library and cannot wait to see what great history Mr. Morgan tells us about in his upcoming works.

Thank you for your hard work and dedication to our countries history Michael!

Sincerely,

Gary S. Smith, Historian

StrangeHistory.org

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1581

Sergeant Richard R. Kirkland: Angel of Marye's Heights

On December 14, 1862, following the Battle of Fredericksburg, Virginia, a legend was born. The actual accounts of the actions of Confederate Sergeant Richard R. Kirkland are brief and vary but one thing remains incontrovertible, Richard Kirkland was the “Angel of Marye’s Heights”.

Richard Rawland Kirkland was born in August of 1849, in the farming community of Flat Rock, located in Kershaw County, South Carolina. As with many young men who resided in rural areas of the south, the chance to march off to war with the Confederate Army served several purposes; The chance to show patriotism for the southern cause and possibly the only chance they would ever have to leave the farm of their birth. Kirkland was one such young man. He mustered into Company E of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry at Camden, South Carolina, under the command of General Joseph B. Kershaw. The unit was quickly dispatched to Fort Moultrie, at the mouth of the Charleston harbor, where Confederates had taken a stance against the U.S. Government. In early July, 1861 the 2nd South Carolina Infantry Regiment began the march toward Virginia where Kirkland and his unit fought battles at Manassas, Savage Station, Maryland Heights and Antietam. Following the Battle of Antietam, Richard Kirkland was transferred to Company G of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry and promoted to sergeant.

The Battle of Fredericksburg pitted General Robert E. Lee’s, Army of Northern Virginia against Major General Ambrose Burnside’s, Army of the Potomac. Burnside had planned to build pontoon bridges across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg and attempt to take the Confederate capitol at Richmond. Lee took up a defensive position at Fredericksburg on December 11, 1864. Two days later, following heavy fighting within the town, the Union Army’s attention was turned toward a ridge on the west side of Fredericksburg known as Marye’s Heights. On the ridge nine thousand confederates under Brigadier General Thomas Cobb and Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw had taken a stand at a four foot high wall on top of the “Heights”. Union forces, under General Edwin V. Sumner, advanced on Marye’s Heights fourteen times, starting at around noon on December 13, and fourteen times they were repelled by the confederates on the Heights. When night fell on Marye’s Heights, approximately seven thousand union soldiers lay dying or dead. Casualties within the confederate line at the Heights numbered only twelve hundred.

As the sun rose over Marye’s Heights on the morning of the 14th the extent of the carnage was clearly visible. Wounded men lay in agony upon the field, in pools of blood surrounded by other fallen Union soldiers. Throughout the morning the moans and groans of the wounded became overwhelming to the Confederates, who had been ordered to hold the wall at the Heights. Sgt. Richard Kirkland, requested permission from his commanding officer, General Kershaw, to tend to the Union wounded, to which Kershaw approved. Kirkland gathered canteens from his fellow soldiers and leapt the stone wall onto the battlefield. For the next two hours the Confederate sergeant made his way from one wounded Union soldier to the next, tending their wounds and giving water to the destitute men. To the amazement of General Kershaw, Sergeant Kirkland was not fired upon by Union soldiers. Kershaw would later give his account of the event.

As the sun rose over Marye’s Heights on the morning of the 14th the extent of the carnage was clearly visible. Wounded men lay in agony upon the field, in pools of blood surrounded by other fallen Union soldiers. Throughout the morning the moans and groans of the wounded became overwhelming to the Confederates, who had been ordered to hold the wall at the Heights. Sgt. Richard Kirkland, requested permission from his commanding officer, General Kershaw, to tend to the Union wounded, to which Kershaw approved. Kirkland gathered canteens from his fellow soldiers and leapt the stone wall onto the battlefield. For the next two hours the Confederate sergeant made his way from one wounded Union soldier to the next, tending their wounds and giving water to the destitute men. To the amazement of General Kershaw, Sergeant Kirkland was not fired upon by Union soldiers. Kershaw would later give his account of the event.

“Unharmed he reached the nearest sufferer. He knelt beside him, tenderly raised the drooping head, rested it gently upon his own noble breast, and poured the precious life-giving fluid down the fever scorched throat. This done, he laid him tenderly down, placed his knapsack under his head, straightened out his broken limb, spread his overcoat over him, replaced his empty canteen with a full one, and turned to another sufferer.”

Sergeant Richard Kirkland would continue to fight for the Confederacy, showing gallantry at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. He met his end at the Battle of Chickamauga while leading an infantry charge up “Snodgrass Hill” on September 20, 1863. It is not known how many lives were saved by Sergeant Kirkland on the battlefield at Marye’s Heights that day, however Kirkland’s actions remain legendary in Civil War history and he will forever be known as the “Angel of Marye’s Heights”.

In researching the story of Sergeant Richard Kirkland, StrangeHistory.org has uncovered a most unusual and coincidental set of historical facts.

Sergeant Richard R. Kirkland (1849-1863) was a non-commissioned officer of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry (1862-1863), a rebel army. He has two monuments dedicated to him, both of which are located in Fredericksburg, Va. He was stationed at Fort Moultrie, SC and died while advancing on an enemy held hill.

Sergeant William Johan Jasper (1750-1779) was a non-commissioned officer of the 2nd South Carolina Infantry (1776-1779), a rebel army. He has two monuments dedicated to him. One located in Savannah, GA, the other in Charleston, SC. He was stationed at Fort Moultrie, then called Fort Sullivan and died while advancing on an enemy held hill.

{fcomment}