- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1586

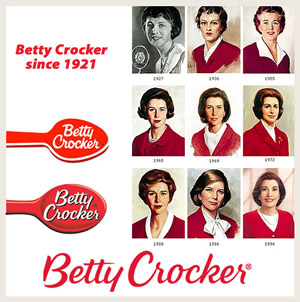

Betty Crocker

Not a real person! The “Betty Crocker” name was presented to the world in 1921 by the advertising executives at Gold Medal flour. It was thought by the team that the name “Betty”, was the most friendly of all of the names considered. “Crocker” originated from William G. Crocker, a Gold Medal executive who had retired only months before the introduction of “Betty Crocker”. The famous Betty Crocker signature was written by an unnamed female employee of Gold Medal.

Dr Pepper (no period behind Dr)

![]()

Not a real person! Dr Pepper stands as the oldest major brand name soda in the United States. It was created by pharmacist Charles Alderton in 1885 and first sold at Morrison’s Old Corner Drug Store, in Waco Texas.

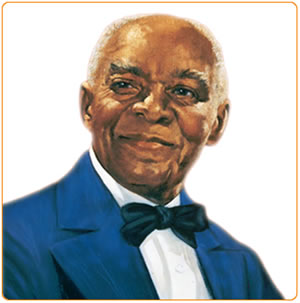

Uncle Ben (Rice)

A real person! (Maybe) Legend tells that the founders of Converted Rice Incorporated were having dinner in a Chicago restaurant and pouring over ideas regarding a new ad campaign. Their waiter told them of an old black rice farmer in Houston, Texas, named “Uncle Ben” who provided “the highest quality rice” to the mills and his customers. Although the “Uncle Ben’s” named has been a part of American food history since 1940, the true origin of Houston’s own, Uncle Ben remains an indelible mystery in America’s Strange History.

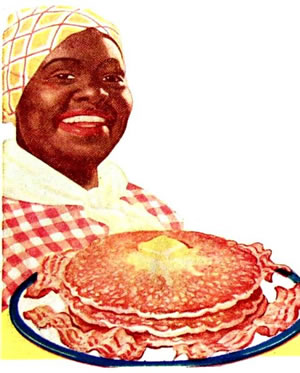

Aunt Jemima

Not a real person! ‘Aunt Jemima pancake mix’ debuted in 1889 and received it’s name from the 1875, Billy Kersand song “Old Aunt Jemima”. The first person to play the “Aunt Jemima” character for the R.T. Davis Milling Company (later purchased by Quaker Oats Company) was a former slave, Nancy Green. Nancy, as “Aunt Jemima”, toured the U.S. representing and demonstrating ‘Aunt Jemima pancake mix’ for thirty-three years, during which she presented ‘Aunt Jemima’ at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Her booth was located next to the “Largest Flour Barrel in the World”.

Sara Lee

A real person! Baking entrepreneur, Charlie Lubin, created a line of cheesecakes which he named “Sara Lee’s” for his eight year old daughter, Sara Lee Lubin. Within a year, Lubin sold his cheesecake recipe and the “Sara Lee” name to Consolidated Foods, presented day Sara Lee Corporation.

Mr. PiBB(two capital B’s)

Not a real person! Mr. PiBB was born from the Coca-Cola Company in 1972. Lawsuits regarding Mr Pibb’s close resemblance to Dr Pepper, caused the company to change the name to incorporate two capital b’s.

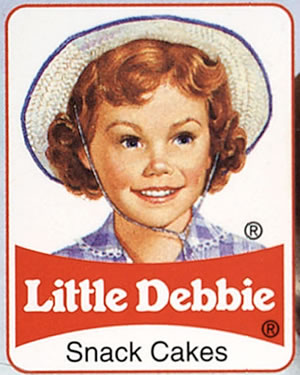

Little Debbie

A real person! The cute girl in a straw hat and blue checked shirt is none other than Debbie McKee, the four year old granddaughter of McKee Foods founder, O.D. McKee. The “Little Debbie” line of snack cakes were first packaged as a family-pack and introduced to U.S. households in 1960, featuring the little Debbie McKee’s likeness. It was then that Debbie’s parents, Ellsworth and Sharon McKee, discovered that their daughter’s name and likeness had been used for the product.

More StrangeHistory.org Food Facts…………….

Campbell’s Soup

In 1900, Campbell’s Soup, which had been founded in 1869 by Joseph A. Campbell, adopted the iconic red and white label with the metallic gold seal and the words, Paris International Exposition. The seal from the 1900 Paris Exhibition while the red and white represents the colors for Cornell University, the alma-ata of Campbell’s executive, Herberton Williams.

Underwood Deviled Ham

The William Underwood Company, founded in 1822, began to can food in steel cans in 1836. William Underwood was the first person to perfect the canning of meats and vegetables for store shelves and holds a place in Strange History as the oldest canner in America.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1893

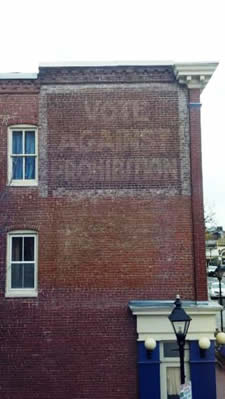

On North Mill Street in Pontiac, Illinois, the International Walldog Mural & Sign Art Museum preserves the murals, hand painted advertisements, and the history of the artists who painted them.

On North Mill Street in Pontiac, Illinois, the International Walldog Mural & Sign Art Museum preserves the murals, hand painted advertisements, and the history of the artists who painted them.

It all started in the late 1880’s when it became very trendy to paint advertisement on the brick wall of a building, old barn, or early billboards. There have been artists who engaged in advertising painting and sign making for centuries, however, the artists who painted on buildings and barns would by 1900 become known as “Wall Dogs.” Some researchers attribute the name to the vast amount of hours that the artists would spend painting from ladders and scaffolding. Hence, “working like a dog!” It would not be long before an entire cottage industry of roaming artists traveling from town to town painting signs, buildings, and barns grew up from the trend.

Around 1895, the President of Coca-Cola Company, Asa Candler, hired a small army of artists to fan out throughout the United States and pay businesses and citizens to paint the familiar Coca-Cola logo on the sides of their buildings and barns. According to most documentation, Coca-Cola Company would continue this pay-and-paint advertising program until the late 1950’s. Many of these hand painted logos can still be found scattered throughout America and, to a small but growing group of preservationists, the faded logos have become roadside attractions. Starting in the early 1990’s, a movement began to restore and repaint the famous Coca-Cola logos.

Around 1895, the President of Coca-Cola Company, Asa Candler, hired a small army of artists to fan out throughout the United States and pay businesses and citizens to paint the familiar Coca-Cola logo on the sides of their buildings and barns. According to most documentation, Coca-Cola Company would continue this pay-and-paint advertising program until the late 1950’s. Many of these hand painted logos can still be found scattered throughout America and, to a small but growing group of preservationists, the faded logos have become roadside attractions. Starting in the early 1990’s, a movement began to restore and repaint the famous Coca-Cola logos.

In 1935 John G. Carter, the owner of the roadside attraction called “Rock City” at Lookout Mountain, Georgia, had his famous logo, “See Rock City,” painted on the sides and roofs of barns. He contracted sign painter and Walldog legend, Clark Byers to deliver a few “See Rock City” logos on barns. Byers, who was being paid by the barn, painted 900 barns in 19 different states.

In 1935 John G. Carter, the owner of the roadside attraction called “Rock City” at Lookout Mountain, Georgia, had his famous logo, “See Rock City,” painted on the sides and roofs of barns. He contracted sign painter and Walldog legend, Clark Byers to deliver a few “See Rock City” logos on barns. Byers, who was being paid by the barn, painted 900 barns in 19 different states.

Coca-Cola and See Rock City are the most prevalent of the early Walldog works, and however faded, these antique advertising paintings can be found on buildings in nearly every town incorporated before 1950. A lead historian for StrangeHistory.org has been on a fifteen year long project to locate and document Walldog advertising. In his research he has found and documented hundreds of hand painted ads including hotels, furniture stores, drug stores, and livery stables. He notes that in some cases he has documented a piece of advertising that was later covered over by the construction of a new building, encasing and preserving the ad for all times.  Furthermore, in an odd case, a one hundred year old building, located in New York, was removed in 2001 revealing a much older hat store advertising on the wall of the adjoining building. The hat store ad was photographed and documented; then another building was constructed encasing the advertisement once again.

Furthermore, in an odd case, a one hundred year old building, located in New York, was removed in 2001 revealing a much older hat store advertising on the wall of the adjoining building. The hat store ad was photographed and documented; then another building was constructed encasing the advertisement once again.

StrangeHistory.org has created an extensive file on Walldog advertisements that exist throughout America, however we can’t find all of them. We are asking our readers, fans, and friends to help us with the very important work of documenting the antique and disappearing wall advertising. In the event your town possesses one of the types of advertisements that you see below, please send a photo of the work and tell us what street and town/city that the fading advertisement can be found.

Thank You

G.S. Smith

StrangeHistory.org.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1613

“The Bearer, Israel Bissell, is charged to alarm the country quite to Connecticut and all persons are desired to furnish him with fresh horses as they may be needed.”

~General Joseph Palmer

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s most famous poem, “Paul Revere’s Ride,” appeared in a Boston newspaper on December 18, 1860. Two days later, South Carolina seceded from the United States government. Many historians have argued that Longfellow was trying to engender a sense of patriotism in the wake of the tumultuous and chaotic Democratic National Convention of 1860. The conventions were held in Charleston and Baltimore, where it became evident that the country’s core political systems were failing. Longfellow recognized that the government “by-the-people” was in trouble and “Paul Revere’s Ride” was penned to remind Americans of the struggles of the founding fathers. With the poem, he created a two hundred thirty-nine year long trail of misinformation, and omitted Israel Bissell, a patriot and post rider who rode three hundred and forty five miles from Boston to Philadelphia spreading the word that the American Revolution had begun.

Longfellow asserts that Revere’s mission was to warn the townsfolk of the approaching British Army. In reality, Paul Revere’s only mission was to ride the twenty miles from Boston to Lexington to warn John Adams and John Hancock. He achieved his mission, and was captured by British soldiers and interrogated by officers for several hours until the first battle of the Revolution erupted on Lexington Green. It was left to the forty or so other riders, including Bissell, to deliver the message of the impending British attacks on the American colonies.

Although Longfellow and the history books forgot Israel Bissell, much is known about the twenty three year old post rider’s gallant five and a half day’s ride to Philadelphia. On April 19, 1775, Bissell, a regular postal rider, was handed a note by General Joseph Palmer of the Massachusetts militia. The note read, “‘To all friends of American liberty, be it known that this morning before the break of day, a brigade consisting of about 1,000 or 1,200 men...marched to Lexington, where they found a company of our colony militia in arms, upon whom they fired, without any provocation, and killed 6 men and wounded 4 others. By an express from Boston, we find that another brigade are now upon their march from Boston, supposed to be about 1,000.’” This message, which announced the beginning of the American Revolution, was to travel in secret with the regular mail service to assure that the rider, Bissell, would not be detained by British soldiers along his route. Legend has that within two hours of departing Watertown, Mass., eight miles from Boston, Bissell had ridden his horse to death.

Although Longfellow and the history books forgot Israel Bissell, much is known about the twenty three year old post rider’s gallant five and a half day’s ride to Philadelphia. On April 19, 1775, Bissell, a regular postal rider, was handed a note by General Joseph Palmer of the Massachusetts militia. The note read, “‘To all friends of American liberty, be it known that this morning before the break of day, a brigade consisting of about 1,000 or 1,200 men...marched to Lexington, where they found a company of our colony militia in arms, upon whom they fired, without any provocation, and killed 6 men and wounded 4 others. By an express from Boston, we find that another brigade are now upon their march from Boston, supposed to be about 1,000.’” This message, which announced the beginning of the American Revolution, was to travel in secret with the regular mail service to assure that the rider, Bissell, would not be detained by British soldiers along his route. Legend has that within two hours of departing Watertown, Mass., eight miles from Boston, Bissell had ridden his horse to death.

Israel Bissell departed Watertown at approximately 10 a.m. on the morning of April 19th and by 9 p.m. had reached Pomfret, Connecticut. For the next three days, Bissell worked his way through Connecticut before arriving on Wall Street in New York City on the morning of the 23rd. He crossed the Hudson River into New Jersey where he presented Palmer’s letter to officials in Elizabeth, New Brunswick, and Trenton. Bissell arrived in Philadelphia at approximately 5 P.M. on the evening of April 24th. Palmer had commissioned Israel to ride as far as Hartford, Connecticut; however, either through sense of duty, the critical nature of the situation, or the belief that his fellow relief riders were loyal to the crown, he decided to continue on to Philadelphia.

Following his heroic ride, Bissell returned to his home in Hartford County, Connecticut, where he joined the Connecticut Militia commanded by Colonel Erastus Wolcott, whose brother Oliver was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. With his brother, Justis Bissell, fighting by his side, Israel served with distinction during the Revolution and earned the rank of sergeant.

Eighty five years after Bissell’s grueling ride from Boston to Philadelphia, Longfellow wrote “Paul Revere’s Ride,” creating an imaginary history that has been interpreted as reality from its inception. Why did Longfellow do it?

It is very unclear why, and theories spin wildly about his misrepresentation of the history of the actual ride of Paul Revere. Longfellow’s writing on the subject has been described as “grossly, systematically, and deliberately inaccurate.” Another question that should be addressed is why the names of Israel Bissell, William Dawes, a Boston tanner and co-rider of Revere’s, and Doctor Samuel Prescott, a local doctor who joined the ride, have been omitted from the ride’s history. Dawes and Prescott escaped the British soldiers who detained Revere, and made their way to Concord to warn the citizens of the impending British attacks.

Perhaps all of these questions can be answered with two simple statements: Longfellow was nothing more than a poet, and nothing else rhymes with Prescott, Dawes, or Bissell!

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 1636

On April 17, 1865, eight days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Union Cavalry Colonel Oscar LaGrange approached the tiny eastern Georgia hamlet of LaGrange. Colonel LaGrange (coincidentally named) and his battle-hardened cavalrymen expected skirmishes with home guard forces in and around Lagrange; however, the small force of horsemen came face-to-face with a “curious, odd, and singular spectacle,” the Nancy Harts.

On April 17, 1865, eight days after General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Courthouse, Union Cavalry Colonel Oscar LaGrange approached the tiny eastern Georgia hamlet of LaGrange. Colonel LaGrange (coincidentally named) and his battle-hardened cavalrymen expected skirmishes with home guard forces in and around Lagrange; however, the small force of horsemen came face-to-face with a “curious, odd, and singular spectacle,” the Nancy Harts.

The Nancy Hart Militia, aka the Nancy Harts, consisted of forty women of LaGrange led by Nancy Hill Morgan and Mary Alfred Heard. They had been established as a militia unit organized to protect LaGrange early in 1861. With the help of Doctor A.C. Ware, the town physician, and a book titled “Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics” published in 1861 by William J. Hardee, the women learned drill and ceremony, battle tactics designed to protect LaGrange from Union invasion, and target practice. Within a few weeks of their inception the women had become superior markswomen, created a chain of command, and named themselves “The Nancy Harts,” in honor of Revolutionary War heroine, Nancy Hart.

Nancy Ann Morgan Hart was born in 1735 in the Yadkin River Valley of Western North Carolina. Shortly after her birth her family moved to the fertile Broad River Valley of Elbert County in north eastern Georgia. She was married at a young age to a Benjamin Hart from a prominent family. Among his descendants are Thomas Hart Benton, U.S. Senator from Missouri, and Kentucky Senator and orator, Henry Clay. Nancy’s family was also well connected to prominent figures in U.S. history. She was the first cousin of Revolutionary War General and later Representative from Virginia, Daniel Morgan. Although little is known about her early years in the Georgia frontier, it is known that Nancy, in adulthood, was a hardened frontierswoman, an excellent shot, feisty and hot headed. She stood nearly six feet tall and was severely scarred from a bout of smallpox and is thought to be, by some historians, crossed eyed. One early account of Nancy Hart states that she possessed, "no share of beauty—a fact she herself would have readily acknowledged, had she ever enjoyed an opportunity of looking into a mirror."

When the American Revolution came to Elbert County, Nancy, a Whig and ardent patriot was already being referred to as “Wahatche” or, “War Woman,” by local Native American tribes. She felt it was her duty to eradicate British sympathizers and Tories from the region. With her husband fighting for the Georgia militia, Nancy would often disguise herself as a man and wander into British encampments to gather information regarding troop movements and battle plans. She is also thought to have been an active participant in the Battle of Kettle Creek on February 14, 1779. In one account of her heroism, British forces descended upon her home demanding food. She sat the six soldiers down and began to feed them. During the meal, Nancy caught the troopers by surprise and took all six captive. Turning the prisoners over to Whig officials, she demanded that they be summarily hung for stealing her food. A subsequent discovery, in 1912, of six skeletons, thought to be over one hundred years old near the site of her former home may substantiate this fabled tale of her intrepidness.

Nancy Hart continued to live in the Georgia frontier with her husband and eight children, six sons and two daughters, until the death of Benjamin in the late 1790s. A few years later, around 1803, Nancy’s oldest son John Hart moved the family to Henderson County, Kentucky. Nancy Hart lived out her remaining years there, passing away in 1830.

Nancy Hart continued to live in the Georgia frontier with her husband and eight children, six sons and two daughters, until the death of Benjamin in the late 1790s. A few years later, around 1803, Nancy’s oldest son John Hart moved the family to Henderson County, Kentucky. Nancy Hart lived out her remaining years there, passing away in 1830.

In the years that have followed her passing, Nancy Ann Morgan Hart has been recognized by Georgia officials as a major figure in the state’s history and has been memorialized numerous times by the state and individual organizations since her death. The Hartwell Dam and Hartwell Lake, created in 1962 and located north of Augusta, Georgia, are both named in her honor. The neighboring county to the north of Elbert County, was renamed Hart County, in honor of Nancy Hart. She is also found memorialized in name by Hart State Park and the Nancy Hart Highway, or Georgia Route 77. The National Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution Milledgeville, Georgia chapter is the Nancy Hart Chapter. In 1997, Nancy was inducted into Georgia Women of Achievement, which recognizes and honors women of Georgia who have contributed to the state’s development. Nancy Hart’s name resides within the GWA alongside that of Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts of America, Helen Dortch Longstreet, environmentalist, author, activist and wife of Confederate General James Longstreet, and Jeannette Pickering Rankin, the first woman elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Then there was the Nancy Hart Militia of LaGrange, Georgia. Upon Colonel LaGrange’s arrival in LaGrange he was met by Captain Nancy Morgan and a line of heavily armed and well organized Nancy Harts. Realizing that the all female militia was vastly outnumbered by the battle hardened Union Cavalry, Captain Morgan called for a formal parlay with Colonel LaGrange where she surrendered the unit and the town of LaGrange. Mrs. Morgan’s charm and hospitality were overwhelming to the Union colonel who, at the behest of Captain Morgan, over tea and cookies, spared the town from total destruction. The ladies who had once held weapons in the defense of LaGrange now bustled about acquiring food for the officers, establishing hospitals, and staffing medical stations for the wounded Union soldiers and Confederate prisoners of war from the Battle of Fort Tyler several days earlier. A plaque was placed in LaGrange by the State of Georgia which reads in part:

The Nancy Harts mobilized promptly, determined to resist any attempted depredations, but they were spared a trial at arms. Seeing the charmingly militant array formed to meet him, Colonel LaGrange complimented them upon their fearless spirit and fine martial air and, after a brief delay, marched on toward Macon, leaving no scar other than the broken railroad to deface this gracious Georgia town whose name he chanced to bear.

For the sake of history, Nancy Ann Morgan Hart should not be confused with Nancy Hart (later Nancy Hart Douglas), the hard riding Confederate markswoman, spy, guide, and guerilla fighter of the North Carolina Moccasin Rangers between 1862 and 1865.

- Details

- Written by: G.S. Strange

- Category: Archive

- Hits: 4427

The Lost Troopers: Beaufort, SC

“The more merciful acts thou dost, the more mercy thou wilt receive.”

-William Penn, Philosopher

Among the headstones of Beaufort, South Carolina’s St. Helena Episcopal Church stands a single stone which denotes the burial site of two officers of the British Army, Lt. William Calderwood and Ens. John Finley. The burial site of Calderwood and Finley, located along the western wall of the churchyard, may be the only two identifiable gravesites, by name and location, of the estimated 47,000 British and Hessian soldiers who died fighting the Patriot army in the American Revolution. The headstone reads:

Among the headstones of Beaufort, South Carolina’s St. Helena Episcopal Church stands a single stone which denotes the burial site of two officers of the British Army, Lt. William Calderwood and Ens. John Finley. The burial site of Calderwood and Finley, located along the western wall of the churchyard, may be the only two identifiable gravesites, by name and location, of the estimated 47,000 British and Hessian soldiers who died fighting the Patriot army in the American Revolution. The headstone reads:

Here lie the bodies of

Lieut. William Calderwood and Ensign John Finley

of Col. Prevost’s British troops.

Killed in Battle near Grey’s Hill Feb. 3, 1779

Buried here Feb. 5, 1779

Rest In Peace

Following a British victory in the First Battle of Savannah on December 29, 1778, British Gen. Augustine Prevost set his sights on taking control of Port Royal and gaining ground one step closer to Charleston. This plan was part of a larger strategy that involved attacking ports in the southernmost point of the colonies and working their way north, taking the busiest ports one at a time and by land. Prevost sent an expeditionary force of 200 battle-hardened troopers of the 16th Regiment, also known as the Queen’s Own Light Dragoons, and the 60th Regiment, also known as the Royal American Regiment, under the command of Maj. William Gardner, to take the town of Beaufort and secure Port Royal Sound, effectively excluding its use by Continental forces.

Gardner traveled by boat from Savannah, landing his troops on present day Laurel Bay Plantation on February 2, 1779. With little or no opposition from Continental forces stationed at Fort Lyttelton, Gardner assumed that taking Beaufort would not be a difficult task; however, communications of the British incursion were sent to Continental Gen. Benjamin Lincoln who immediately dispatched Gen. William Moultrie, the hero of the Battle of Sullivan’s Island, to repel the British. The two armies met near Beaufort, South Carolina on the morning of February 3, 1779.

The British force, consisting of 200 infantrymen, lined up with their backs to a tree line near the top of Grey’s Hill. The Patriot force, consisting of 300 militiamen commanded by Moultrie, three artillery pieces commanded by Thomas Heyward Jr. and Edward Rutledge, both of whom were signers of the Declaration of Independence, and 15 to 20 cavalrymen commanded by Beaufort native Capt. John Barnwell, lined up on open ground below Grey’s Hill. Heyward and Rutledge opened the battle with concentrated cannon fire, consisting of six-pound solid cannonballs and grapeshot, directly into the center and left flank of the British line. In the confusion of the cannon fire, General Moultrie’s militia moved forward to open fire on the British lines with musket shot. The major portion of the battle lasted only 45 minutes, and Major Gardner, facing an overwhelming force and unrelenting cannon fire from the South Carolinians, withdrew from the field, leaving over one-third of his force dead or dying on the battlefield and another dozen troopers captured by the Patriots. Gardner immediately retreated to his boats and returned to Savannah.

The following day, Captain Barnwell was given the gruesome task of burying the 80 British soldiers that had fallen during the battle. It was commonplace during the American Revolution for the Continental Army to bury enemy soldiers where they had fallen or in long trenches, often dug by the British prisoners of war. Therefore, it is unclear how Barnwell decided that the bodies of Lt. William Calderwood, of the 16th Regiment, and Ens. John Finley, of the 60th Regiment, would be removed from the battlefield and placed in the cemetery at St. Helena Episcopal Church. Furthermore, Barnwell’s method of identification of the two officers is unclear. The most obvious explanation is that Barnwell used prisoners of war to identify Calderwood and Finley and that he recognized that the two fallen troopers were officers of the British line deserving of a respectable Christian burial. Upon their burial at St. Helena, Captain Barnwell is reputed to have said, “We have shown the British that we can not only best them in battle but we can also give them a Christian burial.”

In researching this story, StrangeHistory.org researchers discovered that there are no burial sites of British soldiers who died during the American Revolution that are identifiable by name and location in the United States. There are, however, several sites of mass graves of unknown British soldiers that have been located and memorialized with plaques. Calderwood and Finley remain the only two identifiable gravesites of the defeated British Army.

Other plaques to British soldiers who died during the American Revolution read as such:

*Concord, Massachusetts; A plaque erected near the Old North Bridge, in 1910, for two British soldiers reported to have been buried there following the Battle of Concord:

Grave of British Soldiers

They came three thousand miles and died,

to keep the past upon its throne:

Unheard, beyond the ocean tide,

their English Mother made her moan.

April 19, 1775

Cheraw, South Carolina; A plaque erected near St. David’s Church, in 2011, for four unknown British soldiers reported to have been buried in Cheraw, SC.:

Grave of British Soldiers who died during the Revolutionary War

When using St. David’s Church as a hospital in the summer of 1780.

Colonel Campbell, Commander of the 71st (Fraser’s Highland) Regiment is also buried here.

*Note – There are four unknown soldiers buried in the gravesite. Historians have been unable to conclusively identify “Colonel Campbell.” The writers of the original information on the gravesite may have mistaken Col. Archibald Campbell, who is buried at Westminster Abbey, with Capt. Charles Campbell, who was an officer of the 71st Regiment in the summer of 1780.